Pigments from Animals

Cochineal

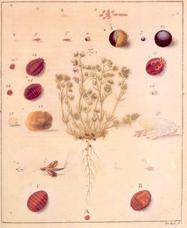

The Cochineal beetle, Latin name Dactylopius confusus, is a small parasitic insect that lives and dines on the prickly pear cactus, or nopal, in Spanish. The insects or, grana are harvested from the cactus and ground into a red pulp. Their blood produces a brilliant red liquid pigment which the ancient Meso-Americans fixed with tin or alum to make a beautiful steadfast dye (Finlay, 2002).

The pigment from the Cochineal was first used by the Inca in frescoes (Finlay, 2002).

The pigment from the Cochineal was first used by the Inca in frescoes (Finlay, 2002).

Because of its non-toxicity, cochineal is still used in many products throughout the world, including the United States. It is commonly used in red lipsticks, and is one of the few red pigments allowed to be used in eye shadow. The color additive in Cherry Coke, E120, is made from cochineal (Finlay, 2002).

Kermes, The Indo-European Cousin of Cochineal

Europe's own Kermes insect, can be one of six scale insects of the Kermes family. Like their American cousins, Kermes insects are parasitic, but colonize on oak trees. Unlike their American cousins, Kermes insects were not ground to a pulp, but instead killed with a vinegar bath or vinegar fumes. The blood of the Kermes insect produces what we know as Carmine red. The blood of the European Kermes insect produced a less intense red than the Cochineal of America, and required ten times as many insects. Kermes insects were used to produce paint, but most often used as a fabric dye (Finlay, 2002).

Tyrian Purple

The most mysterious of the ancient pigments is the dye known as Tyrian purple, named for the ancient town of Tyre were the dye was produced. Tyrian purple was extracted from the Murex, a genus of predatory sea snails. The dye was first exploited by the Phoenicians who killed and scraped the flesh from millions of the tiny sea creatures in order to create the mythic purple robes worn only by ancient royalty and war heroes. According to historical accounts, the dye was collected in huge vats where men stood waist deep in the purple brine, crushing it into a liquid that would then be mordanted with urine and lime to affix to fabric (Finlay, 2002).

Murex and the Roman Empire

The toga of Ancient Rome was not only an article of clothing, it was also a mark of Roman citizenship. Roman emperors declared purple the color of royalty until the end of the Byzantine empire. Only royalty could wear white togas decorated with a brilliant purple band, and only triumphant warriors wore the pure purple toga (Varichon, 2006).

However, during the 19th century the notion of "royal purple" vanished after Sir William Perkin, a burgeoning young chemist at the time of his invention, discovered the first synthetic dyes while attempting to create artificial quinine. Mauve, or, "Mauveine" quickly became an immense fashion trend in Victorian London, and quickly spread to the entire world now that purple textiles were readily available (Garfield, 2000).

However, during the 19th century the notion of "royal purple" vanished after Sir William Perkin, a burgeoning young chemist at the time of his invention, discovered the first synthetic dyes while attempting to create artificial quinine. Mauve, or, "Mauveine" quickly became an immense fashion trend in Victorian London, and quickly spread to the entire world now that purple textiles were readily available (Garfield, 2000).

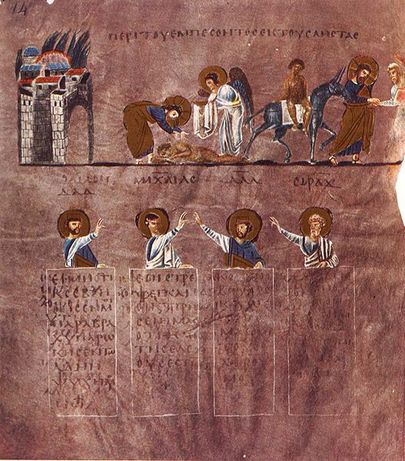

Murex purple was used primarily for textiles and no example survives today. Murex used for dying parchment has greatly faded through the years. An example is the Codex Argenteus, or the "Silver Bible", created in the 6th century. The Codex Argenteus is one of many Codex Purpureus, or purple-dyed parchments used for holy texts during the Byzantine empire. By the 9th century the formula was lost. Historians speculate on what color the dye actually produced. Below, a page from the Rossano Gospels is a surviving example of the original dye.

Mummy Brown

Although the 17th century gave birth to the myth that the pigment Bone Black was made of the remains of charred human corpses, the pigment actualy derived from the burned bones of animals salvaged from the charred scrap pits of slaughter houses. However, the story of the pigment Mummy Brown or "Mommia" is entirely true in all its gruesomeness (Finlay, 2002).

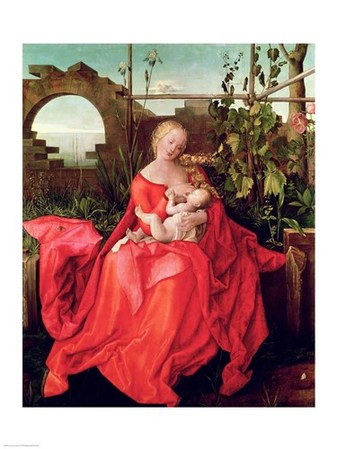

The Egyptian practice of mummifying bodies so that the spirit or Ka might remain whole in the afterlife, involved a process of removing the organs from the deceased body and wrapping it in bitumen and linen. Exploited by 18th century tomb robbers, Mommia became a fad in 18th and 19th century painting. The remains of both human and feline mummies were removed from tombs and shipped to Europe where they were ground into a thick, brown paste and applied to canvases. The pigment was reportedly "excellent for shading"(Finlay, 2002).

The Egyptian practice of mummifying bodies so that the spirit or Ka might remain whole in the afterlife, involved a process of removing the organs from the deceased body and wrapping it in bitumen and linen. Exploited by 18th century tomb robbers, Mommia became a fad in 18th and 19th century painting. The remains of both human and feline mummies were removed from tombs and shipped to Europe where they were ground into a thick, brown paste and applied to canvases. The pigment was reportedly "excellent for shading"(Finlay, 2002).

Although most artworks have not been analyzed for the presence of mummy brown, it is possible for science to employ mass spectrometry in order to identify the signature of human remains (Jones, 2008).